Posted by t

on March 30, 2025, 1:25 pm

on March 30, 2025, 1:25 pm

on March 30, 2025, 1:25 pm

on March 30, 2025, 1:25 pm|

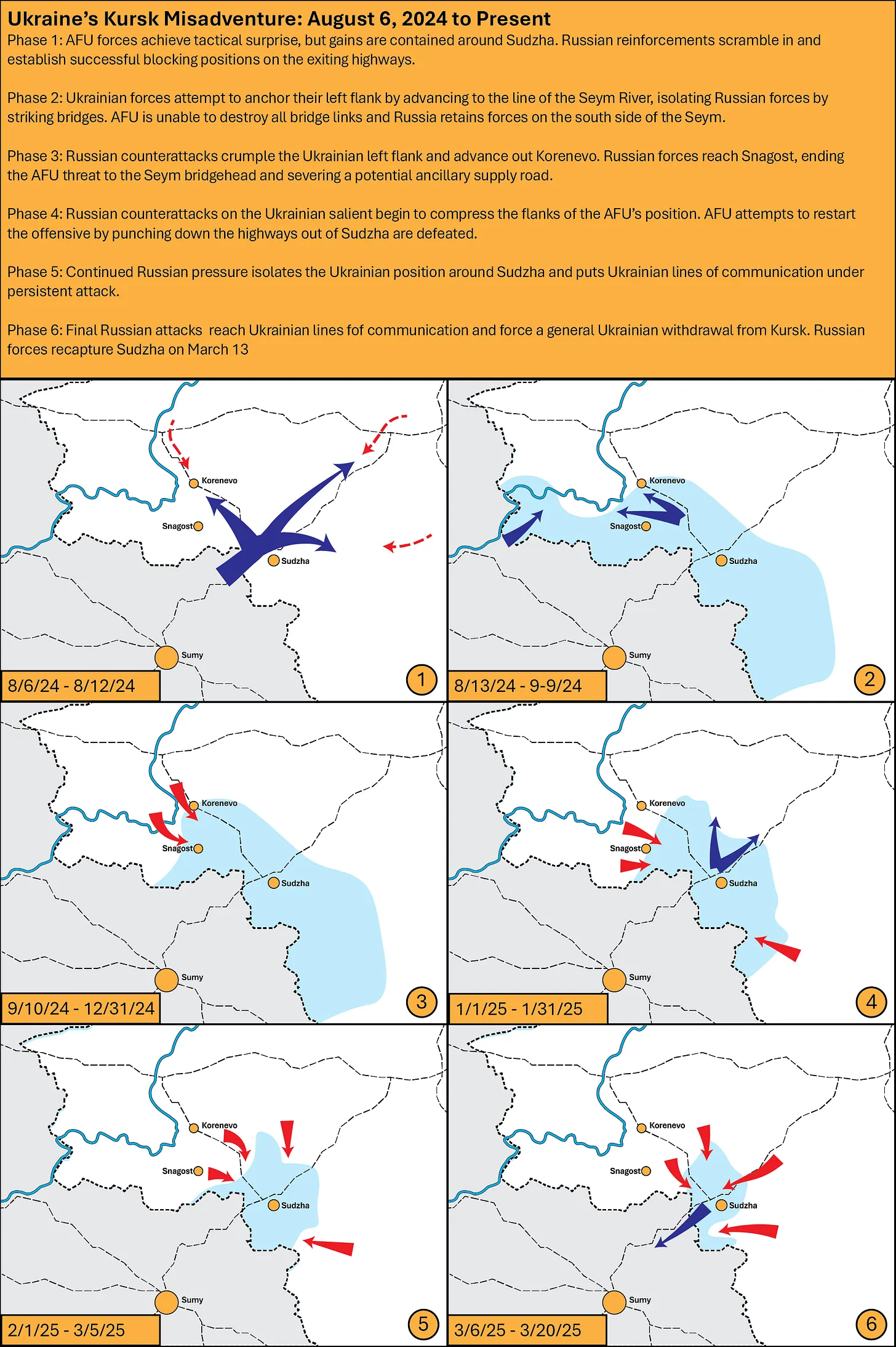

https://bigserge.substack.com/p/ukraine-fighting-to-the-conclusion The Russo-Ukrainian War is now three years old, and the third Z-Day, on February 24, 2025, was marked by a substantively different tone than prior iterations. On the battlefield, Russian forces stand significantly closer to victory than they have at any point since the opening weeks of the war. After reversals early in the war as Ukraine took advantage of Russian miscalculations and insufficient force generation, the Russian army surged in 2024, collapsing Ukraine’s front in southern Donetsk and pushing the front forward towards the remaining citadels of the Donbas. At the same time, 2025’s Z-Day was the first under the new American administration, and hopes were high in some quarters that President Trump could bring about a negotiated settlement and end the war prematurely. The new tenor seemed to be made abundantly clear in an explosive February 28 Oval Office meeting between Trump, Vice President Vance, and Zelensky, which ended in the Ukrainian president being ignominiously shouted down and evicted from the White House. This followed an abrupt announcement that Ukraine was to be cut off from American ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance) until Zelensky apologized for his conduct. In an information sphere rife with rumors, inscrutable diplomatic maneuvering, and heavy handed posturing (clouded further by the distinctive style and personality of Trump himself), it is very hard to figure out what might actually matter. We’re left with a bizarre juxtaposition: based on the explosive vignettes of Trump and Zelensky, many might hope for an abrupt course change on the war, or at least a revision of the American position. On the ground, however, things continue much as they have, with the Russians grinding forward along a sprawling front. The infantryman entrenched near Pokrovsk, listening for the whirring of drones overhead, could be forgiven for not feeling that much has changed at all. I have never made any bones about my belief that the war in Ukraine will be resolved militarily: that is, it will be fought to its conclusion and end in the defeat of Ukraine in the east, Russian control of vast swathes of the country, and the subordination of a rump Ukraine to Russian interests. Trump’s self conception is greatly tied up in his image as a “dealmaker”, and his view of foreign affairs as fundamentally transactional in nature. As the American president, he has the power to force this framing on Ukraine, but not on Russia. There remain intractable gulfs between Russia’s war aims and what Kiev is willing to discuss, and it is doubtful that Trump will be able to reconcile these differences. Russia, however, does not need to accept a partial victory simply in the name of goodwill and negotiation. Moscow has recourse to a more primal form of power. The sword predates and transcends the pen. Negotiation, as such, must bow to the reality of the battlefield, and no amount of sharp deal making can transcend the more ancient law of blood. The Great Misadventure: Front Collapse in Kursk When the history of this war is laid out retrospectively, no shortage of ink will be lavished on Ukraine’s eight month operation in Kursk. From the broader perspective of the wartime narrative, Ukraine’s initial incursion into Russia filled a variety of needs, with the AFU “taking the fight” to Russia and seizing the initiative, albeit on a limited front, after months of continuous Russian advances in the Donbas. Notwithstanding the immense hyperbole that followed the launch of Ukraine’s Kursk Operation (which I facetiously nicknamed “Krepost”, in an homage to the 1943 German plan for its own Battle of Kursk), in the months that followed this was undoubtedly a sector of great significance, and not only because it brought the distinctive of Ukraine holding territory within the prewar Russian Federation. Based on a perusal of the Order of Battle, Kursk was clearly one of the two axes of primary effort for the AFU, along with the defense of Pokrovsk. Dozens of brigades were involved in the operation, including a significant portion of Ukraine’s premier assets (mechanized, air assault, and marine infantry brigades). Perhaps more importantly, Kursk is the only axis where Ukraine has made a serious effort to gain initiative and go on the offensive in the last year, and the first Ukrainian operational level offensive (as opposed to local counterattacks) since their assault on the Russian Zaporizhia line in 2023. With all that being said, March brought about the culmination of a serious Ukrainian defeat, with Russian forces recapturing the town of Sudzha (which formed the central anchor of Ukraine’s position in Kursk) on March 13. Although Ukrainian forces still have a presence on the border, Russian forces have crossed the Kursk-Sumy border into Ukraine in other places. The AFU has been functionally ejected from Kursk, and all dreams of some breakout into Russia have faded. At this point, the Russians now hold more territory in Sumy than the Ukrainians do in Kursk. This would seem, then, to be a good time to conduct an autopsy on the Kursk Operation. Ukrainian forces achieved the basic prerequisite for success in August: they managed to stage a suitable mechanized package - notably, the forest canopy around Sumy allowed them to assemble assets in relative secrecy, in contrast to the open steppe in the south - and achieve tactical surprise, overrunning Russian border guards at the outset. Despite their tactical surprise and the early capture of Sudzha, the AFU was never able to parlay this into a meaningful penetration or exploitation in Kursk. Why? The answer seems to be a nexus of operational and technical problems which became mutually reinforcing - in some respects these problems are general to this war and well understood, while in some ways they are unique to Kursk, or at least, Kursk provided a potent demonstration of them. More specifically, we can enumerate three problems that doomed the Ukrainian invasion of Kursk: The failure of the AFU to widen their penetration adequately. The road-poor connectivity of the Ukrainian hub in Sudzha to their bases of support around Sumy. Persistent Russian ISR-strike overwatch on Ukrainian lines of communication and supply. We can see, almost naturally, how these elements can feed into each other - the Ukrainians were unable to create a wide penetration into Russia (for the most part, the “opening” of their salient was less than 30 miles wide), which greatly reduced the number of roads available to them for supply and reinforcement. The narrow penetration and poor road access in turn allowed the Russians to concentrate strike systems on the few available lines of communication, to the effect that the Ukrainians struggled to either supply or reinforce the grouping based around Sudzha - this low logistical and reinforcement connectivity in turn made it impossible for the Ukrainians to stage additional forces to try and expand the salient. This created a positive feedback loop of confinement and isolation for the Ukrainian grouping which made their defeat more or less inevitable. We can, however, go a little deeper in our postmortem and see how this happened. In the opening weeks of the operation, Ukraine’s prospects became severely untracked by two critical tactical failures which threatened from the outset to spiral into an operational catastrophe. The first critical moment came in the days from August 10-13; after initial successes and tactical surprise, Ukrainian progress stalled as they attempted to advance up the highway from Sudzha to Korenevo. Several clashes took place throughout this period, but solid Russian blocking positions were held as reinforcements scrambled into the theater. Korenevo always promised to be a critical position, as the Russian breakwater on the main road leading northwest out of Sudzha: so long as the Russians held it, the Ukrainians would be unable to widen their penetration in this direction. With the Russian defenses jamming up the Ukrainian columns at Korenevo, the Ukrainian position was already pregnant with a basic operational crisis: the penetration was narrow, and thus threatened to become a severe and untenable salient. At the risk of making a perilous historical analogy, the operational form was very similar to the famous 1944 Battle of the Bulge: taken by surprise by a German counteroffensive, Dwight Eisenhower prioritized limiting the width, rather than the depth of the German penetration, moving reinforcements to defend the “shoulders” of the salient. Blocked at Korenevo, the Ukrainians shifted their approach and made a renewed effort to solidify the western shoulder of their position (their left flank). This attempt aimed to leverage the Seym River, which runs a winding course about twelve miles behind the state border. By striking bridges over the Seym and launching a ground attack towards the river, the Ukrainians hoped to isolate Russian forces on the south bank and either destroy them or force a withdrawal over the river. If they had succeeded, the Seym would have become an anchoring defensive feature protecting the western flank of the Ukrainian position.  The Ukrainian attempt to leverage the Seym and create a defensive anchor on their flank was well conceived in the abstract, but ultimately it failed. By this time, the effects of Ukraine’s tactical surprise had dissipated and there were strong Russian units present in the field. In particular, the Russian 155th Naval Infantry Brigade held its position on the south bank of the Seym, maintained its links to neighboring units, and led a series of counterattacks: by September 13, Russian forces had recaptured the critical town of Snagost, which lies in the inner bend of the Seym. The recapture of Snagost (and the linkup with Russian forces advancing out Korenevo) not only ended the threat to the Russian positions on the south bank of the Seym, but more or less sterilized the entire Ukrainian operation by confining them to a narrow salient around Sudzha and constricting their ability to supply the grouping at the front. It’s rather natural that road connectivity is poorer across the state boundary than it is within Ukraine itself, and this is especially true for Sudzha. Once Snagost was recaptured by Russian forces, the Ukrainian grouping around Sudzha had just two roads connecting it to the base of support around Sumy: the main supply route (MSR in the technical parlance) ran along the R200 highway, and was supplemented by a single road some 3 miles to the southeast. The loss of Snagost condemned the AFU to resupply and reinforce a large multi-brigade grouping with just two roads, both of which were well within reach of Russian strike systems. This poor road connectivity allowed the Russians to persistently surveil and strike Ukrainian supplies and reinforcements making the run into Sudzha, particularly after Russian forces began the widespread use of fiber optic FPV drones, which are immune to jamming. One other advantage of the fiber optic drones, which is not as widely discussed, is that they maintain their signal during final approach to the target (as opposed to wirelessly controlled models, which lose signal strength as they drop to low altitude on attack). The stable signal strength of fiber optic units is a great boon to accuracy, as it allows controllers to control the drone until impact. They also provide a higher resolution video feed which makes it easier to spot and target concealed enemy vehicles and positions. Operationally, the main distinctive of the fighting in Kursk is the orthogonal orientation of effort by the combatants. By this, we mean that Russian counteroffensives were directed at the flanks of the salient, steadily compressing the Ukrainians into a more narrow position (by the end of 2024, the Ukrainians had lost half of the territory they once held), while Ukrainian efforts to restart their progress were aimed at moving deeper into Russia. In January, the Ukrainians launched a fresh attack out of Sudzha, but rather than attempting to widen and solidify their flanks, this attack once again aimed to punch down the highway towards Bolshoye Soldatskoye. The attack was repulsed on its own terms, with Ukrainian columns advancing a few miles down the road before collapsing with heavy losses, but even if it had succeeded it would not have fixed the fundamental problem, which was the narrowness of the salient and the limited road connectivity for supply and reinforcement. By February, the Ukrainian grouping in Kursk was clearly exhausted and their supply linkages were under permanent surveillance and attack by Russian drones. It was perhaps predictable, then, that the Russians would close up the salient quickly once they made a determined push. The actual endgame took, at most, a week of good fighting. On March 6, Russian forces broke through Ukrainian defenses around Kurilovka, to the south of Sudzha, and threatened to overrun the secondary supply road. By the 10th, the Ukrainians were withdrawing from Sudzha proper, with the town falling back under full Russian control by the 13th. It was during this brief period of climactic action that the sensational story of the Russian assault through the pipeline emerged. This become a totem anecdote, with Ukrainian sources claiming that the emerging Russian troops were ambushed and massacred, and Russian sources acclaiming it as a tremendous success. I think this rather misses the point. The pipeline assault was innovative and high risk, and it certainly involved tremendous grit on the part of the Russian troops who had to crawl through miles of cramped pipeline, but ultimately I do not think it mattered much in the operational sense. On a schematic level, the Ukrainian position in Kursk was doomed by mid-September when Russian troops recaptured Snagost. If the Ukrainians had successfully isolated the south bank of the Seym, they would have had the river as a valuable defensive barrier protecting their left flank as well as access to valuable space and additional supply roads. As it happened, the Ukrainian flank was crumpled early in the operation by the Russian victories at Korenevo and Snagost, which left Ukraine trying to fight its way out of a very compressed and road-poor salient. The (correct) Russian decision to concentrate its counterattacks on the flanks further compressed the space and left the Ukrainians with inadequate supply linkages subject to persistent Russian drone strikes. One recent Ukrainian publication claims that by the end of the year, Ukrainian reinforcements had to move to the frontline on foot, carrying all their equipment and supplies, due to the persistent threat to vehicles. Fighting in a severe salient is almost always a bad proposition, and is something of a geometrical motif of warfare going back millennia. In the current operating environment, however, it is particularly dangerous, given the potential of FPV drones to saturate supply lines with high explosive. In this case, the effect was particularly synergistic: the cramped salient amplified the effect of Russian strike systems, and this in turn prevented the Ukrainians from assembling and sustaining the force needed to expand the salient and create more space. Confinement bred strangulation, and strangulation bred confinement. Fighting with a caved in flank for months, the Ukrainian grouping was doomed to operational sterility and eventual defeat almost at the outset. The world is still adjusting to the new kinetic logic of the powerful ISR-Strike nexus which now rules the battlefield. What Kursk demonstrates, however, is that conventional sensibilities about operations are hardly obsolete: if anything, they have become even more important in the age of the FPV drone. Ukraine’s defeat in Kursk ultimately reduces to well-established rules about lines of communication and flank security. Their early defeats in Korenevo and Snagost left their western flank permanently crumpled and thrust them back on a thin logistical chain which was easy for Russian forces to surveil and strike. In a sense, drones have made it possible to vertically envelop enemy forces, isolating frontline groupings with persistent overwatch on supply roads. This was a feature that was largely missing in Bakhmut, where Russian forces were still preferentially using tube artillery rather, but it seems to be a permanent feature of the battlefield going forward, making seemingly antiquated concerns like “lines of communication” more important than ever. Drones matter, but the spatial position of forces matter too. So where does this leave Ukraine? They’ve now blown a pair of carefully husbanded mechanized packages: one in Zaporizhia in 2023, and now a second in Kursk. In both cases, they were unable to cope with the capability of Russian strike systems to isolate their groupings on the frontline, and with Russian surveillance and strikes on rear assembly areas and bases of support. Their position in Kursk is gone, and they have nothing to show for their efforts. All theories as to why Ukraine went into Kursk are now a quaint point of speculation. Whether or not they intended to hold some token slice of Russian territory as a bargaining chip is irrelevant, as the slice is gone. More importantly, the theory that Kursk could force a major redeployment of Russian forces has gone awry and now threatens to boomerang on the Ukrainians. Most of the Russian forces in Kursk were redeployed from their grouping in Belgorod, rather than the critical theater in the Donbas (as we noted earlier, while the AFU was running its “diversion” in Kursk, the Russians completely collapsed the southern Donetsk front and pushed up the Dnipro Oblast border). What’s important to note, however, is that the Kursk front is not going to be scratched off simply because the Russians have ejected Ukraine across the border. In his surprise appearance at the Kursk theater headquarters, Putin noted to need to create a “security zone” around Kursk. This is the Russian parlance for continuing the offensive across the Ukrainian border (and in fact, Russian forces have crossed into Sumy Oblast in several places) to create a buffer zone. This will have the dual purpose of both keeping the front active, preventing Ukraine from redeploying forces back to the Donbas, and preempting any attempt by the AFU to stage forces for a second crack at Kursk. Most likely the Russians will attempt to capture the heights along the border line and position themselves uphill from the Ukrainians, replicating the situation around Kharkov. In short, having opened a new front in Kursk, the Ukrainians cannot now easily close it. For a force facing severe personnel shortages (read my previous analysis on the parlous state of Ukrainian mobilization if you’d like a refresher), Ukraine’s inability to shorten their frontline creates unwelcome additional stresses. With Russian pressure continuing unabated in the Donbas, we are left wondering whether a doomed 9 month battle for Sudzha was really the best use of Ukraine’s dwindling resources. A Brief Tour of the Front The Kursk salient is the second front to be fully collapsed by the Russian Army in the past three months. The first was the southern Donetsk front, which was completely caved in over the course of December and then rolled up in the opening weeks of the year, which had the effect of not only knocking the AFU out of longstanding strongholds like Ugledar and Kurakhove, but also safeguarding the flank of the Russian advance towards Pokrovsk. At the moment, there are several axes of Russian progress which we’ll examine in more detail momentarily. More broadly, as Russia scratches off secondary axes like South Donetsk and Kursk, the general trajectory of the front is becoming more focused, as the arrows converge on the Slovyansk-Kramatorsk agglomeration. Eyes on the prize. Russia currently controls roughly 99% of Lugansk Oblast and 70% of Donetsk. Etc |

|

Responses

|