![]()

on October 30, 2025, 7:01 pm, in reply to "The Duran: Burevestnik negates US geography advantage"

on October 30, 2025, 7:01 pm, in reply to "The Duran: Burevestnik negates US geography advantage"

“They have produced something new.”

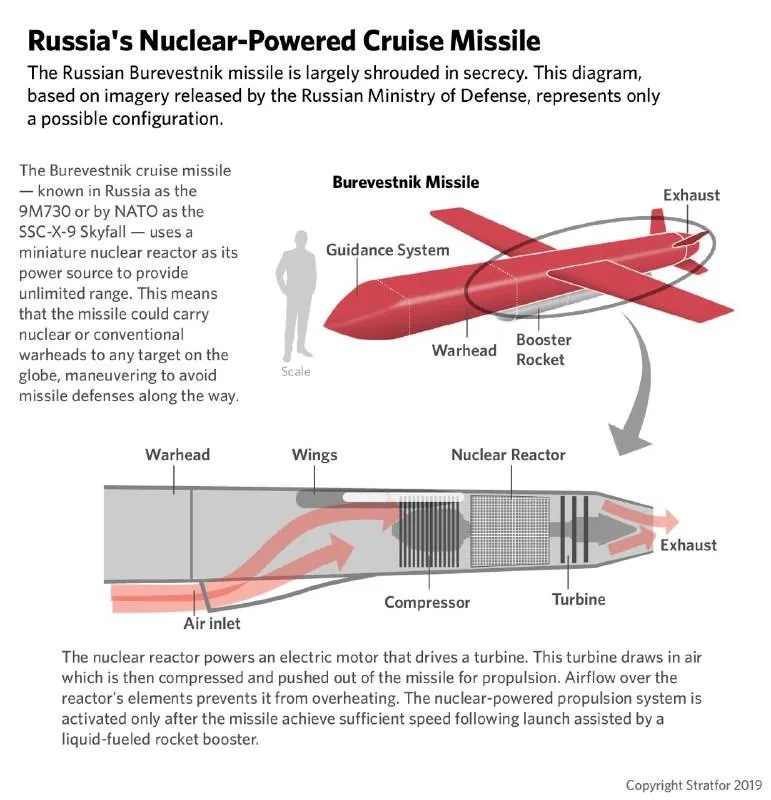

On 26 October, Russian President Vladimir Putin was briefed on a test of the nuclear-powered, purportedly unlimited-range cruise missile known as Burevestnik (Буревестник “Storm petrel“). Designated 9M730 in the GRAU index and identified by NATO as SSC-X-9 Skyfall, Russian authorities have presented the system as capable of defeating contemporary air- and missile-defense architectures and of delivering a nuclear payload across intercontinental distances.

Western analysts and media responded to the Burevestnik tests with notable alarm and skepticism. Jeffrey Lewis, a nuclear-nonproliferation scholar at Middlebury College, described the system provocatively as a “little flying Chernobyl,” calling its emergence “a bad development” for the United States and arguing that the weapon would be “destabilizing and difficult to address within arms-control frameworks.” The New York Times characterized President Putin’s announcement as “a stark signal to the West” following the collapse of a planned summit with former U.S. President Donald Trump. Norwegian military intelligence publicly confirmed that the tests occurred in the Novaya Zemlya archipelago in the Arctic Ocean; Vice Admiral Nils Andreas Stensenes, head of Norway’s intelligence service, stated that Norway “can confirm that Russia conducted a new test launch of the Burevestnik long-range cruise missile on Novaya Zemlya.”

Some commentaries amplified worst-case scenarios. Military Watch Magazine asserted that Burevestnik could “lurk in the sky for years” before striking unpredictably, and some accounts suggested it might be capable, in principle, of circumglobal transit. Former U.S. Army officer Stanislav Krapivnik argued that a deployed capability of this kind would complicate—and substantially raise the cost of—continental missile-defense architectures such as the U.S. Golden Dome concept, which he claimed would need far denser coverage to compensate for proliferated approach vectors. Such assertions vary widely in technical plausibility and should be treated with caution: public discussions mix verified reporting, expert inference, and speculative extrapolation, and independent technical corroboration of many of the more dramatic claims is lacking.

Development of the program reportedly began in December 2001, with flight testing initiated around 2016–2017. The name Burevestnik (“Storm Petrel”) was formally adopted in March 2018 following a public vote hosted on the Ministry of Defense website. According to official statements, the most recent test occurred on 21 October 2025.

Although described in official statements as a nuclear-powered cruise missile, the Burevestnik’s precise technical parameters remain undisclosed. Limited official footage and a small number of public images provide only a general impression of its external configuration; consequently, most assessments draw on informed inference from visual material and contextual data. The system, therefore, remains the subject of considerable conjecture, with state media, independent analysts, and various commentators on social networks advancing competing reconstructions of its design and capabilities.

Most of the missile’s tactical and technical characteristics remain classified and will likely remain so for the foreseeable future. Nevertheless, open reporting and analytical commentary permit the development of a provisional technical profile. Burevestnik is commonly described as an experimental, subsonic or near-sonic cruise missile powered by a compact onboard nuclear reactor rather than by conventional hydrocarbon or solid propellants. It is reported to operate at low altitude, to exhibit extended endurance and global-range potential—speculative estimates have suggested operational radii exceeding 20,000 km—and to possess in-flight trajectory flexibility. Open-source outlets such as Voennoe Obozrenie have published unverified figures placing speeds at 850–1,300 km/h and altitudes of approximately 25-100 meters.

Russian official statements and imagery assert that the missile’s exterior dimensions are broadly comparable to those of the Kh‑101 cruise missile and that it incorporates a compact nuclear powerplant, with a claimed range that is orders of magnitude greater than that of the Kh‑101. Official footage depicts ground launches from an inclined transport‑and‑launch container using rocket boosters.

Observers and independent commentators offer more detailed — and not always consistent — estimates. Pavel Ivanov of Military‑Industrial Courier described the missile as “one and a half to two times larger in size than the Kh‑101,” noting a high‑mounted wing configuration (as opposed to the Kh‑101’s low‑mounted wings) and “distinctive protrusions” visible in video footage that he interprets as housings related to air‑heating by a reactor. Ivanov further estimated that the Burevestnik’s mass is several times, and possibly an order of magnitude, greater than that of the Kh‑101.

Nezavisimaya Gazeta reported that the missile uses a solid‑fuel booster and a nuclear air‑breathing sustainer engine, and offered nominal dimensions of approximately 12 m at launch and 9 m in cruise configuration, with an elliptical frontal cross section on the order of 1.0 × 1.5 m. All such figures remain unverified and should be treated as provisional: they derive from media reporting, visual scaling of released footage, and expert judgment rather than from independently released technical specifications. If you would like, I can convert this into a short, annotated summary listing the primary open‑source claims and the degree of corroboration for each.

The novelty claim and historical precedents

The principal novelty claimed for Burevestnik is its nuclear propulsion; however, nuclear propulsion for atmospheric flight is not without precedent. Long-range subsonic and strategic cruise concepts date to the early Cold War and include programs such as the U.S. SM-62 Snark. Those projects combined extended endurance with autonomous navigation but achieved only coarse accuracy by contemporary standards. They illustrate the long-standing technical challenge of reconciling strategic range with acceptable precision, and they underscore the historical importance of celestial, terrain-referenced, and other correction techniques in improving guidance performance.

During the late 1940s through the 1960s, the United States also investigated nuclear-propelled cruise concepts—most prominently Project Pluto and the associated SLAM (Supersonic Low Altitude Missile) design—which sought to employ nuclear reactors or reactor-heated propulsion to enable essentially unlimited endurance. Although reactor and propulsion testing were carried out, those programs were canceled in the 1960s owing to extreme technical complexity, environmental and safety concerns, and the rapid maturation of intercontinental ballistic missile technology that diminished the strategic utility of nuclear-powered cruise systems.

Available accounts suggest that the Burevestnik powerplant is conceptually closer to a reactor-heated uniflow turbine or an open-cycle gas-turbine architecture than to closed-cycle designs; however, public reporting is fragmentary and program details remain classified. Independent technical estimates that compare the system to conventional cruise-missile benchmarks place the reactor’s non-thermal useful power in the hundreds of kilowatts—within the projected envelope of contemporary compact reactor concepts—but these figures are necessarily speculative in the absence of verified program data.

The Soviet Union also developed its own concept of the rocket and aviation nuclear engine (NRE). The classical operating principle of a nuclear missile engine or how it is called in Russian “Ядерный ракетный двигатель (ЯРД![]() )” is straightforward: nuclear fuel heats the reactor core to the maximum temperature that the structural materials will safely permit, and a heat exchanger transfers that thermal energy to a working fluid. Once heated, the working fluid expands and is expelled through a nozzle into the surrounding medium, producing thrust. Candidate working fluids include low-molecular-weight substances such as hydrogen and helium, as well as water vapor and other light gases. NRE concepts exist with both solid and gas‑phase reactor cores. In the gas‑phase (or “open‑core”) variant, the achievable exhaust velocity of the working fluid may exceed that of contemporary liquid‑propellant rocket engines by an order of magnitude for a comparable thrust level, but realizing such performance incurs extreme engineering difficulties. Solid‑core NREs are technically less challenging to implement and nevertheless deliver specific impulses several times greater than those of conventional chemical rockets; for these reasons, historical and contemporary research has concentrated primarily on solid‑core designs.

)” is straightforward: nuclear fuel heats the reactor core to the maximum temperature that the structural materials will safely permit, and a heat exchanger transfers that thermal energy to a working fluid. Once heated, the working fluid expands and is expelled through a nozzle into the surrounding medium, producing thrust. Candidate working fluids include low-molecular-weight substances such as hydrogen and helium, as well as water vapor and other light gases. NRE concepts exist with both solid and gas‑phase reactor cores. In the gas‑phase (or “open‑core”) variant, the achievable exhaust velocity of the working fluid may exceed that of contemporary liquid‑propellant rocket engines by an order of magnitude for a comparable thrust level, but realizing such performance incurs extreme engineering difficulties. Solid‑core NREs are technically less challenging to implement and nevertheless deliver specific impulses several times greater than those of conventional chemical rockets; for these reasons, historical and contemporary research has concentrated primarily on solid‑core designs.

Operational implications and doctrinal effects

Unlike conventional cruise missiles, whose range is constrained by fuel load, a nuclear-propelled propulsion system would be principally limited by the operational lifetime and survivability of the reactor and its associated systems. In practical terms, this implies greatly extended loiter times, the ability to traverse considerable distances without refueling, and the capacity to change routing or to patrol until favorable conditions for attack materialize. From a doctrinal perspective, these attributes could allow approach vectors that exploit gaps in surveillance or early-warning coverage—including polar or southern approaches—and would complicate the tasking of cueing networks and interceptor systems.

Defenders of this assessment emphasize three interrelated effects that could make interception more difficult. First, prolonged endurance and unpredictable routing undermine early-warning and cueing networks that assume predictable launch points and trajectories. Second, a low-altitude flight profile reduces detectability by some sensor classes and increases the cost and complexity of continuous tracking. Third, in-flight maneuverability reduces the applicability of interceptor solutions optimized for ballistic or otherwise predictable flight paths. Analysts such as Felix Lemmers have argued that Burevestnik, if realized as described, would combine attributes usually associated with strategic long-range systems and low-observable strike platforms, producing a hybrid threat that challenges existing taxonomies. Other specialists, including Dennis Gormley, have noted that the combination of endurance and maneuverability would impose substantial economic and technical burdens on any state attempting to field a comprehensive, reliable missile-defense network.

Evidentiary record, critiques, and vulnerabilities

Public reporting indicates a mixed experimental record. By early 2019, some foreign sources reported numerous test events of varying success; following the October 2025 test, Russian General Valery Gerasimov reported that the missile had traversed roughly 14,000 km in about fifteen hours and executed required vertical and horizontal maneuvers. Russian authorities announced preparatory steps to establish infrastructure for deployment while acknowledging that further development remained necessary before operationalization. Norwegian intelligence subsequently identified the test area in the Novaya Zemlya archipelago. Western media widely framed the test as a geopolitical signal.

Technical and operational challenges temper optimistic appraisals of battlefield effect. The presence of an onboard reactor may create detectable signatures—radiation anomalies that space-based or airborne sensors could detect—thus producing a novel class of cueing data for adversary surveillance. Subsonic speeds and extended transit times increase the temporal window in which a detected vehicle can be engaged; airborne radar platforms, interceptors, or other assets could locate and destroy a missile in flight if detection occurs with sufficient lead time. Safe recovery, handling, and peacetime basing of a reactor-equipped vehicle also introduce significant logistical, safety, and legal complications. In the absence of reliable recovery procedures, non-combat losses would pose proliferation, environmental, and political risks.

Technical architecture and engineering challenges

Open imagery and factory footage indicate storage in polygonal transport-and-launch containers with lifting end caps and suggest ground-based launches assisted by solid-fuel boosters. Test articles filmed in workshop footage are often painted red—characteristic of prototypes to aid visual inspection—and flight footage captured from escorting aircraft has been circulated in multiple releases:

The project’s most novel element appears to be an air-breathing gas-turbine/jet architecture integrated with a compact nuclear reactor. Thermal energy from the reactor would plausibly be transferred via heat exchangers to an engine working fluid or directly to intake air; the resulting heated flow would then be exhausted through a nozzle. Such an arrangement could resemble a reactor-augmented turbojet (an open-cycle configuration) or a closed/intermediate cycle that uses a primary coolant loop to transfer heat to a conventional turbine. No verified schematic of the powerplant has been published; among the publicly discussed possibilities, an air-breathing reactor-heated cycle is most consistent with the reported subsonic flight regime.

Because the missile is intended for very long flights, its guidance suite must integrate multiple modalities: satellite navigation (GLONASS in the Russian context), inertial navigation, and terrain-referenced navigation for midcourse correction. For strikes against preselected fixed targets, this layered approach obviates the need for an autonomous terminal seeker that searches for targets; instead, the weapon can rely on stored route data and periodic position corrections to maintain acceptable accuracy over prolonged sorties. Robust mission management for multi-day flights also implies secure datalinks for mission updates and re-tasking or, alternatively, sophisticated preprogrammed decision logic to handle contingencies in radio-silent environments.

From an engineering standpoint, several propulsion topologies present trade-offs. Open-cycle designs, in which intake air passes through the reactor core, are thermodynamically simple and can offer high thermal efficiency but would produce radioactive exhaust. Closed-cycle designs limit radioactive emissions but add complexity, mass, and reliability challenges. Material selection for high-temperature fuel elements and heat-exchanger components is critical; refractory ceramics and advanced composites have historically been proposed to enable compact, high-temperature reactor cores.

Navigation and mission management over oceanic stretches depend primarily on satellite positioning and redundant inertial and astro-inertial systems to mitigate jamming or signal loss. On approach to land, terrain-referenced navigation and preloaded three-dimensional corridor models permit periodic correction points, enabling position updates while maintaining radio silence between corrections. Such layered navigation reduces detectability and improves terminal accuracy for strikes against predetermined fixed targets.

The Reactor

On 3 March 2021, TASS, citing a military‑diplomatic source, reported that tests had been completed on a small‑sized nuclear powerplant that could be applied to both cruise‑missile and underwater‑vehicle programs. The announcement has been widely cited in open‑source commentary as evidence of progress on compact reactor modules, but the report itself provides no technical specifications and does not identify the reactor architecture tested.

In an independent, open‑source estimate, Jeff Terry (physics professor, Illinois Institute of Technology) analogized the powerplant to the Tomahawk cruise missile and calculated a plausible, useful (non‑thermal) power of about 766 kW. Terry noted that this magnitude of shaft or propulsive power falls within the broad envelope of what modern compact reactor concepts could, in principle, deliver; however, his figure is an inference based on analogy and scaling rather than a measurement of any publicly disclosed system.

At present, the reactor type used in the program is uncertain; nonetheless, informed assumptions can be made based on contemporary developments in compact reactor technology. The most immediate hypothesis invokes a liquid-metal-cooled architecture. It is worth noting that liquid-metal cooling is not an experimental novelty in the Russian–Soviet tradition: earlier Soviet work explored liquid-metal reactors for submarine propulsion (for example, programs associated with the Project 705 (705K) series), and those historical efforts provide a plausible technical lineage for current compact-reactor thinking. Taking a liquid-metal concept as a working baseline, therefore, permits a focused discussion of likely design trade-offs and system constraints without presuming access to classified programmatic details. Importantly, this is an exercise in conceptual inference rather than in technical specification.

The prospect of powering a small cruise missile with a micro nuclear reactor hinges on exploiting the exceptional energy density of nuclear fuel to decouple vehicle endurance from the mass of chemical propellant. In conceptual terms, a reactor-based powerplant replaces the finite energy stored in fuel tanks with a compact source of thermal power whose operational duration is governed by fuel burnup, materials lifetime, and systems survivability rather than by an on-board hydrocarbon load. This change in the primary limiting parameter transforms mission concepts: endurance extends from hours to days or longer, routing may be dynamically altered during flight, and the operational envelope can incorporate prolonged loitering and wide-area patrol. These doctrinal possibilities, however, are tightly constrained by a nexus of engineering, detection, safety, legal, and logistical factors that together determine practicability.

From an architectural perspective, reactor-driven propulsion concepts for atmospheric platforms fall into broad families distinguished by how thermal energy is extracted and converted to useful propulsive work. Open-cycle approaches transfer reactor heat directly to the intake air stream and expel that air as thrust; these arrangements maximize thermodynamic simplicity and specific energy conversion but risk dispersing radioactive products if the working fluid contacts reactor internals. Closed-cycle or intermediate-cycle arrangements instead use a primary coolant loop contained within the reactor to transport heat to a secondary working fluid or to a power conversion system; such schemes reduce or eliminate direct radioactive contamination of the exhaust but add mass, complexity, and potential failure modes in heat-transfer interfaces. In either case, the core issues are the same: achieving a sufficiently compact core and associated heat-exchange hardware that provide the required thermal power density while surviving launch loads, vibration, thermal transients, and the radiation environment, and doing so within a mass and volume budget compatible with the intended airframe and launcher.

Liquid-metal cooling is often proposed as an enabling technology for compact reactors because certain liquid metals combine high thermal conductivity, low vapor pressure at elevated temperatures, and favorable heat capacity per unit volume. In contrast to water-based systems that require high pressure to achieve high-temperature operation, liquid-metal coolants can operate at comparatively low system pressure while effectively transporting heat from the core to heat exchangers. This permits smaller pressure vessels, reduces the need for heavy structural reinforcement, and supports higher operating temperatures, thereby improving thermodynamic conversion efficiency. From an engineering standpoint, liquid-metal coolants offer attractive trade-offs for applications that require compactness and high heat-flux handling.

Nevertheless, liquid-metal coolants introduce distinct materials and systems demands. Many candidate liquid metals are chemically reactive with air or water. They can corrode or embrittle common structural alloys, driving the need for specialized claddings, compatible piping, and rigorous sealing—factors that increase technical complexity and manufacturing cost. Liquid-metal systems also pose unique chemical and radiological contamination challenges if the coolant circulates through regions that become activated by neutron flux; managing activated coolant, preventing leaks during handling, and ensuring remote maintenance capability become nontrivial design drivers. Furthermore, the thermal expansion characteristics and freezing points of some liquid metals impose operational constraints for ground handling and staging prior to launch; systems must be tolerant of thermal transients and provide safe cooldown paths without exposing personnel or the environment to contamination. These attributes complicate any effort to adapt civilian microreactor concepts—designed for inspectable, serviceable installations—to the extreme mass, stealth, and robustness requirements associated with airborne weapon systems.

Heat-to-thrust or heat-to-electricity conversion is another critical trade-off axis. Directly using reactor-heated air for propulsion can yield higher system simplicity and energy density, but increases the difficulty of controlling radiological emissions. Alternatively, converting reactor heat to shaft power via a closed Brayton or Stirling-like architecture, and then driving a turbine or propulsor, reduces exhaust contamination but requires massy turbomachinery, bearings, and high-temperature seals that must be qualified for shock, vibration, and wide temperature excursions. The added mass of such conversion systems reduces the net endurance advantage and imposes greater structural and aerodynamic demands on the airframe. In addition, controls and instrumentation that regulate reactor power, control flow rates, and respond to transient conditions must be exceptionally robust; failure modes in these subsystems can lead to catastrophic outcomes and therefore necessitate conservative design margins and redundant safety functionality that further increase mass and complexity.

Operational survivability and detectability form an intertwined set of constraints. Reactor operation produces physical signatures beyond conventional thermal and radar cross-section considerations. Neutron and gamma emissions, activation of surrounding structures, and, for open-cycle designs, isotopic particulates entrained in exhaust flows create unique observables that can be sensed by suitably equipped spaceborne, airborne, or maritime sensors. Passive radiological monitoring, combined with multispectral thermal and radio-frequency surveillance, can therefore be leveraged by defenders as an additional cueing channel. While low-altitude, terrain-following flight profiles reduce detectability against certain radar geometries, they increase exposure to ground-based electro-optical and infrared sensors and to increasingly networked, persistent airborne sensor networks. Moreover, slower subsonic transit velocities—likely for weight-limited, reactor-powered small vehicles—lengthen the temporal window in which engaged sensors can task interceptors or use distributed sensor fusion to localize a contact. Thus, endurance does not equate to invulnerability; instead, it shifts the sensor–shooter balance and the economic burden between both attacker and defender.

Safety, environmental, and logistical factors exert powerful constraints both during peacetime testing and in operational deployment. The airborne carriage of a radioactively fueled core elevates the consequences of non-combat losses. The potential for radiological release in crash scenarios or for the dispersal of activated coolant in the event of structural failure creates transboundary environmental liabilities with acute diplomatic and legal implications. Ground infrastructure for assembly, fueling, storage, and maintenance of reactor-equipped vehicles would require specialized facilities, tightly controlled personnel access, and emergency response capabilities that go well beyond the logistical footprint of conventional missile programs. International norms and treaties, as well as national regulatory frameworks designed around stationary reactor installations, present additional hurdles; routine flight testing that risks atmospheric release of radioactivity would likely provoke significant international condemnation and legal responses.

Material science and component qualification are central technical bottlenecks. Fuel forms, cladding materials, and heat-exchanger surfaces must tolerate high temperatures, neutron flux, and mechanical stress over mission-relevant lifetimes. Refractory alloys and ceramic composites have been investigated in other compact-reactor contexts because of their ability to maintain structural integrity at high temperature, but these materials introduce manufacturing and joining challenges, and their behavior under rapid thermal cycling and ballistic mechanical loads is not trivial to predict. Similarly, seals, valves, and bearings that operate in proximity to the core must resist radiation-induced degradation, and the need for maintenance-free operation over relatively long intervals imposes stringent reliability requirements that tend to penalize mass and complexity when redundancy is introduced.

From a systems-integration viewpoint, thermal management must be reconciled with airframe aerothermodynamics, structural stiffness, and mass distribution. Concentrated heat sources alter local material creep rates and can create thermal gradients that drive distortion; the design must therefore account for thermo-mechanical coupling in the vehicle’s structural and control surfaces. The integration of shielding presents another design compromise: sufficient shielding reduces dose to sensitive electronics and personnel during handling but adds mass that reduces payload and endurance. Passive shielding materials also change the vehicle’s center of gravity and inertial properties, affecting flight control law design and launcher compatibility.

On the defensive and policy side, the existence—even as a demonstration—of reactor-powered propulsion for small vehicles would drive investment in tailored detection and attribution capabilities. Spaceborne instruments that combine spectral radiometry with gamma and neutron sensing, airborne platforms with deployable radiological monitors, and maritime patrol assets with integrated multisensory suites would form a layered detection architecture. Attribution becomes a practical and legal mechanism: detection of a radiological signature over international waters can be used by states to mount diplomatic protests, impose sanctions, or pre-emptively alter force posture. Thus, the purported operational advantages of reactor propulsion must be weighed against the heightened political visibility and legal exposure they entail.

Finally, the cost–benefit calculus is dominated by the interdependence of the above issues. Engineering solutions that mitigate one class of vulnerabilities typically exacerbate other constraints. Reducing radiological signature through closed-cycle designs and heavier shielding increases mass and reduces endurance margins. Improving reliability via redundant control systems and hardened components increases production and sustainment costs. Mitigating environmental risk through elaborate containment and recovery procedures imposes logistical burdens that reduce the operational agility of the force fielding such systems. These trade-offs have been evident in historical programs that explored airborne nuclear propulsion and remain salient today.

In conclusion, while the physics underlying the use of micro nuclear reactors and liquid-metal cooling for compact airborne applications is well understood at a theoretical level, translating that understanding into a practical, safe, and politically tolerable capability faces substantial, interconnected obstacles. Liquid-metal cooling offers measurable thermodynamic and packaging advantages for compact reactors but brings attendant materials, contamination, and handling challenges. Conversion of reactor heat into propulsive power without unacceptable environmental release or prohibitive mass penalties remains the central engineering dilemma. Even if technical hurdles were overcome, detectability, international legal constraints, logistical complexity, and the high costs of robust, safe deployment would make such systems strategically niche rather than transformative. Any continued discussion of these concepts must therefore remain focused on policy, detection, verification, and risk-mitigation research rather than on operational design or construction details. If you would like, I can convert this material into a referenced review with open-source citations focused on historical programs, microreactor literature, liquid-metal coolant properties, and sensor/detection approaches; I will keep any follow-up strictly non-actionable.

Political, environmental, and normative considerations

The program raises complex environmental and diplomatic questions. Extended test flights and potential operational use would involve transits over large oceanic areas; prolonged operation of an open-cycle reactor in international airspace would generate radiological and diplomatic concerns. The development and production of reactor-based propulsion substantially increase acquisition and lifecycle costs relative to conventional cruise missiles. Although the principal technical advantage remains endurance and routing flexibility, these gains come with increased complexity, safety burdens, and potential ecological liabilities.

From an operational-political perspective, demonstrations of an operable nuclear-powered missile serve signaling and deterrent purposes: they reinforce claims of strategic parity and complicate adversary planning. Nevertheless, analysts, including Konstantin Sivkov, characterize reactor-powered cruise missiles as niche systems that would complement rather than replace established delivery platforms. They would introduce new command-and-control, basing, and maintenance burdens and would necessitate reconsideration of arms-control, legal, and environmental regimes in the event of accidents or misidentification.

Conclusion

Publicly available evidence supports the conclusion that a nuclear-powered cruise-missile concept exists and that flight and reactor-module testing have been undertaken. Yet significant obstacles remain before the concept can be translated into a fully operational, reliably deployable weapon. Key technical challenges include reactor miniaturization and thermal management, qualification of high-temperature structural and fuel materials, development of reliable closed-loop or low-emission propulsion architectures, and robust navigation and guidance for long-endurance missions. Equally salient are ecological, legal, and diplomatic constraints associated with prolonged reactor operation in atmospheric flight.

The trade-offs are substantial: a reactor-driven cruise missile potentially offers endurance and routing flexibility beyond the reach of fuel-limited systems, but at the cost of greater complexity, expense, and environmental and political risk. Until such challenges are resolved and independently verifiable performance data are published, claims of operational invulnerability should be treated with caution.

In any case, the Burevestnik story in this article is just the beginning… The next is the Poseidon…

Responses « Back to index | View thread »